17 Oct GOLDEN AGE OF CELTS: STATUS BUILT BY BATTLE OR FEAST

The whole race [Celts] is made for war. High-spirited and quick to battle.

— Strabo, Greek Historian

Introduction

The following is a reblog of a post entitled, “Golden Age of Celts: Status Built by Battle or Feast,” that was originally posted on February 25, 2014 as the beginning of a series that discusses the history of the ancient Celts that stretched the regions of Ireland, Northern Europe, and Turkey from 500 BC to 500 AD.

GOLDEN AGE OF CELTS

Status-Building in Battle

During the Golden Age of the Celts (Le Tène Period), cattle thievery, slave raiding, and vendettas between clans and tribes formed the basis of low-intensity warfare that permeated the Celtic society. Such conflicts were a starting point for a young warrior to demonstrate his bravery and skills at weapon-handling. In a society that took personal courage for granted, something more was required to establish a reputation.

One way was to serve as a mercenary in many of the various armies during the classical period. Renowned Celtic mercenaries served Hannibal during his invasion of Italy in the Second Punic War. The Celtic invasion helped establish Rome’s image of Celts as fierce warriors. They also fought in Greek armies and successor kingdoms following the break-up of Alexander’s empire in Egypt.

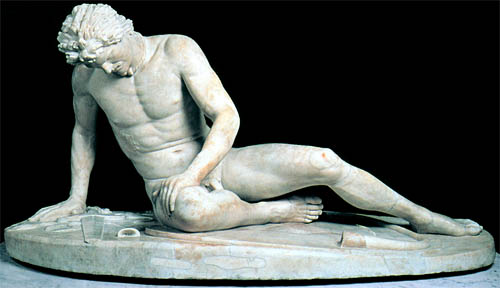

Statue of Dying Celtic Warrior

A distinct group of Celtic mercenaries called the Gaesatae joined the Cisalpine Gauls in the battle of Telemon against the Romans. These mercenaries were outside the normal social structure of the clan and tribes. The Celtic word geissi—bonds, taboos, or sacred rule of conduct—suggests these warriors had a strong spiritual aspect to their life, which will be further examined in later posts. It was the custom of Gaesatae to fight naked in battle as a ritual act.

Location of Battle of Telemon

Clearly, many Celts looked for fame and future in the lucrative Mediterranean world with the hope of returning home with their reputations established. Mercenary service also removed young warriors from the tribe when their drive to achieve high status was at their most intense.

Potlach

Previous posts highlighted that trade with the Mediterranean had a significant impact on Celtic society. Nobles rewarded warriors and other clients with foreign luxuries, the value of which was measured by the influence it could command by giving it away. This method of redistributing prestigious items to increase status is called potlatch.

The 1st Century BC Greek historian, Poseidonius, writes that Lovernius, a Celtic noble who attempted to win popular support by driving his chariot across his territory and distributing gold and silver to those who followed him. Moreover, a noble set-up separate enclosures one and one-half miles on each side. He filled vats with expensive liquor and prepared food for all who wished to feast—an important social gathering that was not unlike today’s celebrations. The feasts were usually wild and drunken, but strict ritual rules were obeyed.

Celtic Roundhouse for Assembly

Wild Celtic Feasts

Strict ceremonial rules were observed for seating participants according to rank and prowess. Poseidonius describes the arrangement as follows:

“…they sit in a circle with the most influential man in the center, whether he is the greatest in warlike skill, was the nobility of family or wealth. Beside him sat the host, and on either side of them were others in order of distinction. Their shield bearers stood behind them while the spearmen were seated on the opposite end. All feasted in common with their lords.”

Central Hearth in Celtic Roundhouse

Also in attendance were bards who sang praises of their patrons’ lineage, bravery, and wealth. Their songs could praise and satirize their patron, thus encouraging nobles and warriors to be even more generous during the feast. Strangers could also share the meal before they were asked their name and business.

Celtic Swords Displayed at British Museum

Everyone had a piece of meat according to their status. Traditionally, the greatest warrior had the choicest cut, consisting of the thigh. When the hindquarters were served, another warrior could claim it and fight in single combat to the death against the champion to elevate his status. Others sought to reinforce their status through mock battle engagement that might escalate into more serious violence, possibly death.

Conclusions

According to Caesar, the bravery of the Celts sprang from their lack of fear of death. This was because Celtic believed the soul does not die. The classical authors, Caesar, Lucan, and Diodorus Siculus, in particular, emphasized the Celtic belief in metempsychosis. At death, the soul passes from one body to another in reincarnation. This belief may, in part, explains why Celts felt it was important to establish their status in preparation for the journey to the Otherworld.

Not only did Celtic men fight bravely in battle, but historical accounts and mythology provide evidence that women held equal standing to men and often fought in battles and served as military and spiritual leaders. This will be discussed in the next post.

References:

John Davies, The Celts: Prehistory to Present Day; 2005. United States: Sterling Publishing Co., New York.

Stephen Allen, Celtic Warrior: 300 BC-AD 100; 2001. Osprey Publishing LTD., Westminster, MD, USA.

Julius Caesar, translated by F. P. Long, 2005. The Conquest of Gaul; United States: Barnes & Noble, Inc.

©Copyright February 25, 2014, by Linnea Tanner. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Jan Sikes

Posted at 08:03h, 18 OctoberFascinating information, Linnea! Thank you for sharing!

Linnea Tanner

Posted at 13:56h, 18 OctoberThank you, Jan, for your comment! Hope you have a lovely week!

Rita Roberts

Posted at 02:58h, 19 OctoberHi Linnea, Only yesterday I was reading this very subject from an A Level course I did way back in 1988 and enjoyed it so much, just as I have enjoyed this post but of course enhanced with wonderful pics, The photo of the dying Gaul is very touching. Thank you for sharing

Linnea Tanner

Posted at 11:30h, 20 OctoberHi Rita, Thanks for commenting on my post and the photos. It’s fun to learn that you read about this information back in 1988. Most of the information is taken from archaeologists’ books, which adds so much to the historical accounts. The dying Gaul is one of my favorite statues. I hope you have a fantastic week!

Luciana

Posted at 00:26h, 25 OctoberThe statue of the dying Gaul alway evokes the struggles, despair and defeat of a proud leader. Excellent article, Linnea.

Linnea Tanner

Posted at 11:40h, 25 OctoberThank you, Luciana, for your comments. I’m also touched every time I see this statue. I hope you have a fantastic week!