13 Sep Celtic British Kings #CelticKings #BritishKings #JuliusCaesar #LinneaTanner #Britannia

“In our sleep and in our dreams, we pass through the whole thought of earlier humanity.

The dream carries us back into earlier stages of human culture and affords us a means of understanding it better.”

—Friedrich Neitzsche

Introduction

The following is a reblog of the post entitled, “Celtic British Kings,” which was first published on 21 November 2015 on my website. The backdrop of my historical fantasy series, Curse of Clansmen and Kings, will span from 24 AD through 40 AD during the reigns of Roman Emperors Tiberius and Caligula. Below is the historical background of the series.

Celtic British Kings

Even before Caesar’s military excursions into Britannia (ancient Britain), ambitious Celtic kings ruled over tribal kingdoms in the southeast, lowland areas. Julius Caesar wrote that Britannia was a land similar to Gaul where parts of the population were divided into named units of tens of thousands of people. Caesar called these civitates, translated as ‘tribes’, though ‘states’ would have been a more appropriate description.

Map Ancient Britannia

The Celtic societies of Britannia were dominated by the military and the religious elite. Nobles considered themselves as part of wider Aristocracies that defined the larger ‘ethnic’ groups. Rank and religion were important in governing life. The inhabitants served empire-building rulers and royal dynasties that carved out fiefs.

Caesar’s most formidable foe in his invasions was Cassivellaunus. Caesar described him as a warlord and ‘robber-barron’ with no named people attached to him. His territory north of the Thames coincides with the powerful tribe later known as the Catuvellauni. It is interesting to note that most of the ‘named’ tribes Caesar mentioned in the 50s BC vanished a century later. This suggests instability and volatility of dynasties played a crucial role in triggering the Roman invasion by Claudius in 43 AD. The actions of some of these British rulers suggest their primary interests were personal power rather than the collective interest of their people.

British and Gallic Connection

Britannia was intimately interconnected to northern Gaul (modern-day France) well before Caesar’s time. Caesar writes that ‘within living memory,’ that Diviciacus, ruler of the Belgic Suessiones, exerted power on both sides of the English Channel. This suggests the importance of the dynastic links and the personal nature of power in Britannia. Caesar further reports that identical tribal names were found in both Gaul and Britannia, although he does not identify them.

Archaeological findings from burial sites provide further evidence of wealthy and privileged aristocrats ruling in Britannia before Caesar’s invasions. Luxury objects found in some of the tombs were more about feasting and drinking and less about war. The burial rites and grave goods were Gallic imports or imitations. The richest graves are found near settlements such as Camulodunum (Colchester) which were more urbanized.

Linnea Tanner Beside Ancient Roman Wall in Colchester

Lowland Britannia was integrated into a wider political, economic, and cultural zone that spanned the British Channel and reached toward the Rhone Valley and the Alps. Some graves also contain war jars and drinking vessels from Rome even before Caesar invaded southeast Britannia.

Caesar’s first two expeditions (55 – 54 BC) failed to bring the Britons under the direct rule of Rome. Nonetheless, Rome was a powerful political force that some British rulers relied on to resolve their internal squabbles. British nobles often found alliances with the Romans in line with their interests.

Replica of Roman Dining Area at Fishbourne Roman Palace Built by Celtic King

Rome’s first emperor, Augustus, established administrative systems in Gaul. A network of roads and river transport opened the trade of ceramics, glass, wine, and oil manufactured in Rome throughout the arteries of Gaul. Widespread trade was aided by a common currency, language, and bureaucracy that was unhindered by the old patchwork of Celtic tribal rivalries. The Thames estuary was the new gateway into Britannia and the tribes who controlled the entrance dominated access to continental luxuries.

Augustus most likely maintained diplomatic links with Britannia to ensure the southeast remained in the hands of friendly tribes. To the north was the ambitious and aggressive Catuvellauni tribe (the name means ‘Men Good in Battle’). To keep them in their place, Rome cultivated their southern neighbors and rivals, the Atrebates. Commius’ sons (as they describe themselves on their coins) seem to have befriended Rome while mired in sibling rivalry. Tincomarus, the ‘Big Fish’ was ousted by Epillus in AD 7 and Epillus in turn by Verica in AD 15. Augustus was indifferent to their domestic squabbles, as long as the Atrebates stayed loyal to Rome and the balance of power was not disturbed. To the Romans, northern Britannia and Ireland beyond the trading gateway were remote and irrelevant.

Roman Wall Calleva (Silchester)

At the time of Claudius’ invasion in 43 AD, there was not a united British resistance because some tribes fought fiercely with each other. Many client kings in Britannia openly welcomed the Romans or at least quickly came to terms. There was a striking difference between the rapid incorporation of lowland Britain into the Roman Empire and the slower conquest of highland regions.

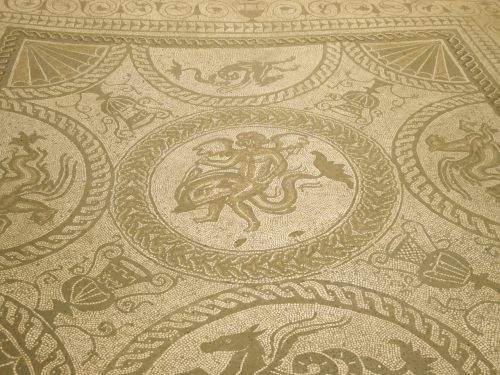

Cupid Dolphin Mosaic Floor at Fishbourne Palace Built by Pro-Roman Celtic King

It took the Romans a generation to conquer what would be considered Wales and northern England while Scotland and Ireland were never incorporated at all. Hadrian’s Wall which was built in 122 AD was an admission of failure.

Hadrian’s Wall in Northern England

Celtic Kings Southeast Britain

Coin evidence is no substitute for detailed political accounts; nevertheless. it provides us with the earliest names of the players in the 1st-century British power struggle. As a form of propaganda, the coins provide a hint of tribal territories, alliances, and political geography of southern Britannia in the decades before the Romans invaded in 43 BC.

The Catuvellauni to the north of the Thames, and the Atrebates, to the south, became the dominant tribes at the time Augustus brought stability to Gaul beginning in 30 BC. Below is a map that provides the location of major Celtic tribes in Southeast Britain at the time of Rome’s Invasion of Britannia in 43 AD:

- Atrebates, Belgae, Cantiaci, and Regni (South of Thames)

- Trinovantes and Catuvellauni (North of Thames).

Map of Ancient Britannia 1st Century AD

The primary capitals of these Celtic tribal territories were Durovernum (Canterbury; Cantiaci), Camulodunum (Colchester; Catuvellauni & Trinovantes), Verulamion (St. Albans; Catuvellauni), Calleva (Silchester; Atrebates), and Noviomagus (Chichester; Regni)

After Caesar’s invasions, the most powerful British rulers began minting coins inscribed with their names. The pro-Romans rulers were permitted to inscribe the Roman title ‘Rex,’ meaning ‘king’ on the coins. Epillus, for example, issued coins with the inscription ‘rex calle[vae] – King of Calleva. Verica emblazoned a vine leaf on his coins, a reflection of his identification with the Mediterranean culture. Below is a list of rulers who were either recorded in Roman accounts or minted coins between Caesar’s and Claudius’ invasions.

| Date | Rome | Southern Dynasty | Northern Dynasty |

| 50 BC | Caesar’s Invasion | Mandubracius, Cassivellaunus | |

| 40 BC | Assassination of Caesar | Commius | |

| 30 BC | Octavian & Antony Civil War | ||

| 20 BC | Augustus Stabilization | Tincomarus | Addedomaros, Tasciovanus |

| 10 BC | Eppillus | Cunobelin, Dubnovellaunos | |

| AD 10 | Tiberius | Vodenos | |

| AD 20 | Epatticus | ||

| AD 30 | Caligula | Verica | Adminius |

| AD 40 | Claudius | Caratacus, Togodumnus |

To be continued

The next series of posts will describe the political struggles of pro- and anti-Roman rulers between Caesar’s expeditions in 55 – 54 BC and Claudius’ invasion in 43 AD.

References

David Miles, The Tribes of Britain, Phoenix, Imprint of Orion Books, Ltd., London, UK, 2006.

Graham Webster, Boudica: The British Revolt Against Rome AD 60, Reprinted 2004 by Routledge, London.

Simon James, The Atlantic Celts: Ancient People or Modern Invention; The University of Wisconsin Press, 1999.

Friedrich Neitzsche, Human, All Too Human, vol. I, p. 13; cited by Jung, Psychology and Religion, par. 89, n. 17.

©Copyright November 21, 2015, by Linnea Tanner. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Rita Roberts

Posted at 06:42h, 13 SeptemberHi Linnea, I do so love this period in time of the Romans in Britain,However I am not sure I would have liked living in those times.The Romans could be pretty brutal But I love all their colour, their decor and their wonderful mosaics, their architecture and they certainly knew how to build roads. Great post thanks for sharing.

Linnea Tanner

Posted at 11:53h, 13 SeptemberI appreciate your comments, Rita, on my post. I agree the Romans were brutal, but they left their imprint on Britain as evidenced by the archaeological finds at Bath and Fishbourne Palace. Hope you keep safe and stay well!

Luciana

Posted at 00:55h, 20 SeptemberFascinating article, Linnea, though the Romans would never admit to failing or that Hadrian’s Wall was built to protect the conquered Roman settlements in Britain!

Linnea Tanner

Posted at 09:26h, 20 SeptemberThanks, Luciana, for commenting. It’s quite amazing to see how much of Hadrien’s Wall remains intact to this day, although it’s been nearly 1500 years since the Romans left. Hope you are doing well and staying safe, my friend.