23 Aug Cunobelin Celtic British King

Introduction

The following is a reblog of a post entitled, “Cunobelin Celtic British King”, which was first published at this website on February 4, 2016. Cunobelin and his sons, Adminius and Caratacus, are actual historical figures on which characters in the historical fantasy series, Curse of Clansmen and Kings, are based. The article provides the historical backdrop on which the series is based.

________________________________________________

One thing that comes out in myths is that at the bottom of the abyss comes the voice of salvation. The black moment is the moment when the real message of transformation is going to come. At the darkest moment comes the light

—Joseph Campbell

Cunobelin Celtic British King

Cunobelin was considered the greatest of all of the Celtic British kings. The Romans referred to him as Britannorum Rex, the King of the Britons. He is also known as Cunobeline and Cunobelinus. He is the radiant character in Shakespeare’s Cymbeline and Geoffrey of Monmouth’s The History of the King of Britain written in 1136 AD. It is not clear where Cunobelin came from, but his rise to power was rapid and dramatic. He gained his throne in the early 1st century AD as a young man in his twenties or early thirties.

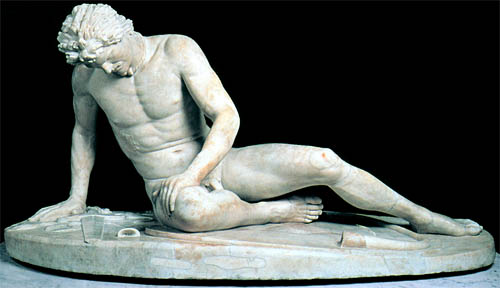

Statue of Dying Celtic Warrior

Overview of Celtic Kings in Southeast Britain

Below is an overview of Roman events and Celtic kings in Southeast Britain between Julius Caesar’s invasions in 54-55 BC and Claudius’ invasion in 43 AD.

Cunobelin’s Rise to Power

Cunobelin claimed he was the son of Tasciovanus, the Catuvellauni ruler whose center of power was at Verulamium (present-day St. Albans). Upon his father’s death, Cunobelin gained power over the Catuvellauni. He then moved against the Trinovantes and extended his kingdom to the east. His father may have had an alliance between the two powerful tribes, possibly by dynastic marriage. It is also possible that he seized the throne in a palace revolt. He expanded his territory to the west and southward into Kent.

Cunobelin’s rise to power occurred at the same time that Roman Emperor Augustus had significant resistance in Germania that took higher precedence. In 9 AD, three Roman legions led General by Publius Quinctilius Varus were crushed by the Germanian Prince Arminius—a disaster of unparalleled magnitude. Augustus and his advisers were too preoccupied with the events to pay much attention to political upheavals in Britain. Cunobelin must have known he could act without any serious threat of Roman reprisals. An astute statesman, he gave assurance to Rome that the balance of power was not seriously affected. Roman traders were still welcome in Camulodunum (modern-day Colchester) and elsewhere north of River Thames.

Roman Soldiers in Formation

Balancing Pro and Anti-Roman Factions

Geoffrey of Monmouth writes Cymbeline (i.e. Cunobelin) was a warlike man and insisted on the full rigor of the law. He was reared in the household of Emperor Augustus Caesar. Cunobelin was so friendly with the Romans that he might as well have kept back their tribute-money but paid it of his own free will. In the photograph of the Roma Ara Pacis Altar below, there is a little boy between Agrippa (Augustus’s son-in-law) and Livia (Augustus’s wife). The boy’s mother is shown in the background patting his head. Although this boy might be Agrippa’s son Lucius (born 17 BC) and the woman his mother Julia, he wears a tunic and Celtic neck-torc instead of a toga and is thus probably a barbarian prince. It is known that many children of foreign monarchs lived in the imperial court.

Celtic Child in Roma Ara Pacis Procession Hard Particolare

Cunobelin had to maintain a balance between two bitterly opposing factions for, and those against, Rome. In view of the expulsion of the pro-Roman rulers, Tincommius and Dubnovellaunos, around 8 AD, Cunobelin had to be careful throughout most of his reign not to show undue bias towards Rome. There were strong anti-Roman elements by Druids in the royal household. During his lifetime, Cunobelin successfully satisfied his own people, as well as persuading Rome of his loyalty while keeping the power of the Druids in check.

Camulodunum Oldest Recorded City

Cunobelin moved his capital to Camulodunum. It was considered the oldest recorded town in Britain, as it was mentioned by Pliny the Elder who died in 79 AD. The Celtic settlement was huge compared to hill forts to the west or north. Cunobelin minted his coins at this town to exploit trading with the Continent. The grave goods found in this area illustrate the impact of Rome on Camulodunum’s nobles in the early 1st Century. Items found included chain-mail armor, Roman bronze vessels, furniture, wine amphorae, and a medallion encasing a silver coin of Augustus, minted about 17 BC.

The nobles sustained their power and their lifestyles on the back of hard-working peasantry. Power was maintained by warriors whose loyalty had to be constantly rewarded. To maintain luxurious lifestyles, the Celtic rulers raided inland Britain for slaves. Neck chains used to restrain slaves have been found around Colchester and are on display at the museum in Colchester. Strabo notes that some British leaders procured the friendship of Augustus by sending embassies and paying tribute to him.

Cunobolin’s Expansion into Kent

Cunobelin expanded his influence into Kent, which became a fiefdom ruled under his son, Adminius. Durovernum (modern-day Canterbury). Like Verulamium and Camulodunum, the town functioned as a center for the elite, a gateway for Roman luxury goods, and a base for traders from the empire.

Mosaic Panel from Durovernum

Cunobelin had several sons of whom three, Togodumnus, Caratacus, and Adminius played significant roles triggering the Roman invasion in 43 AD. In Cunobelin’s final years, he had trouble over the succession. His sons shared administrative duties for various parts of his kingdom. In Cunobelin’s declining years, it is likely Rome became uneasy with the political uncertainties. It became increasingly clear that the valuable commercial asset in Britain needed to be secured either by renewing treaties with the new rulers or by

Coinage minted by Adminius suggests that he ruled the Northeast part of Kent on behalf of his father a short time before his death. Adminius held pro-Roman sympathies whereas his brothers were anti-Roman. Emperor Caligula may have secretly collaborated with Adminius to set up a major seaborne operation to invade Britain. This could have been the reason that Cunobelin expelled Adminius from Britain in 40 AD. Suetonius records the banished prince with a group of his followers fled to a Roman encampment where Caligula was reviewing the troops in Germania. Caligula retained the Britons as hostages and dispatched a message to Rome proclaiming he had conquered the whole of Britain.

Caligula on a Horse

Subsequently, Roman troops appeared ready to invade Britain, but it is not clear what stopped the expedition. Possibly the troops rebelled and refused to embark the warships. Infamous for his bizarre behavior, Caligula paraded the troops in battle array on the shore and commanded them to collect seashells. Though the Roman invasion was abandoned, Caligula erected a great lighthouse at Boulogne. It stood as a memoir of this event until it was torn down in 1544 AD.

Frieze of Roman Warship

The precise date of the death of Cunobelin is not certain, but it must be within a year of 40 AD. This is when Caractacus conquered territories south of the Thames while Togodumnus inherited the kingdom. The flight of Adminius may be connected with these events.

Caratacus overthrew Verica, King of the Atrebates who also sought protection from the Romans. Verica appeared before Emperor Claudius claiming he had been driven out of Britain by an uprising. He called upon the Emperor to fulfill his obligation to reinstate him as a ruler under their treaty. Caratacus demanded that Claudius release Adminius and Verica to him—the final trigger that incited Claudius to invade Britain in 43 AD.

References:

Geoffrey of Monmouth, “The History of the Kings of Britain.” Translated with an Introduction by Lewis Thorpe; First Published in 1966; Republished by Penguin Books, London England

David Miles, “The Tribes of Britain”, published in 2006 by Phoenix, an imprint of Orion Books, LTD, London.

Graham Webster, “Boudica: The British Revolt Against Rome AD 60, Reprinted 2004 by Routledge, London.

Graham Webster, “The Roman Invasion of Britain.” Reprinted in 1999 by Routledge, New York.

Joseph Campbell, “The Power of Myth with Bill Moyers.” Anchor Books, a Division of Bantam Doubleday Dell Publishing Group, New York, 1988.

©Copyright February 4, 2016, by Linnea Tanner. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Rita Roberts

Posted at 02:53h, 23 AugustGreat post Linnea I love the history of the Romans in Britain and their problem with the Celts. Hope all is well with you Stay safe during these trying times. Hope a lovely week!

Jan Sikes

Posted at 08:28h, 23 AugustA very thorough and fascinating look at the history of Cunobelin and that era! Thanks for sharing, Linnea!

Linnea Tanner

Posted at 16:51h, 23 AugustThank you, Jan, for reading my post and commenting. It’s a period of history that I like to piece together with the limited written accounts. Hope you stay safe and healthy during these difficult times. Have a lovely day.

Christy Birmingham-Reyes

Posted at 19:50h, 23 AugustI always learn so much from your blogs, Linnea!

Linnea Tanner

Posted at 10:14h, 24 AugustThank you, Christy, for your comments. One of the pleasures of writing is doing research and learning more about ancient civilizations. Hope you are doing well and staying safe, my friend.

Yvette M Calleiro

Posted at 08:28h, 24 AugustI’ll be honest. History doesn’t filter into my brain very well. Lol! But I loved the pictures and map. 😉

Linnea Tanner

Posted at 10:26h, 24 AugustI appreciate your comments, Yvette, as it is sometimes difficult to filter through history and piece together what happened from various historians. However, history has modern-day relevance because, as George Santayana quoted, “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” What remains consistent throughout history is human nature and what drives people to do what they do. Hope you stay safe and healthy. Have a wonderful week!

Bill Wilson

Posted at 03:45h, 12 SeptemberVery interesting! Thanks for sharing!

Linnea Tanner

Posted at 12:03h, 12 SeptemberThank you, Bill, for commenting. Have a lovely day!