21 May Caesar’s 2nd Invasion Britain 54 BC (Part 3)

THE STANDARD PATH of the mythological adventure of the hero is represented in the rites of passage: separation—initiation—return. A hero ventures forth from the world of common day into a region of supernatural wonder where fabulous forces are encountered and a decisive victory is won, then the hero comes back from this mysterious adventure with the power to bestow advantage on his fellow man—Joseph Campbell

Introduction

The following is a reblog of a post published on May 20, 2013 about Caesar’s 2nd invasion of Britannia. The epic historical fantasy series, Curse of Clansmen and Kings, is set in Britannia (modern-day Great Britain), Gaul (modern-day France), and Ancient Rome and spans the period from 24AD to 40AD prior to the invasion of Claudius in 43AD. This is Part 3 of the historical and archaeological evidence that supports the theory that Julius Caesar’s invasions of southeast Britannia (55-54BC) help establish Celtic tribal dynasties loyal to Rome. The political unrest of rival tribal rulers in 24AD sets the backdrop to APOLLO’S RAVEN (Book 1 Curse of Clansmen and Kings) where the Celtic warrior princess, Catrin, first meets the great-grandson of Marcus Antonius (Mark Antony).

Statue of Julius Caesar Displayed at Louvre

Caesar’s 2nd Invasion Britain

Prelaunch Preparations Redesign Ships

Due to the frequent tidal changes that Caesar encountered in his first expedition to Ancient Britannia in 55BC, he ordered his generals to construct smaller transports with shallower drafts for easier loading and beaching. The vessels’ beams were built wider to carry heavy cargoes, including large numbers of horses and mules. As a result of the redesign, the clumsy ships were difficult to maneuver and thus were equally fitted for rowing and sailing. It was not clear from Caesar’s accounts whether the purpose of this second exhibition was to conquer Britannia, to punish hostile tribes, or to open the isle to Roman trade. The unfolding events in his accounts suggest the primary objective was to establish pro-Roman dynasties that would be subsequently rewarded with lucrative trade for their loyalty.

Replica of Ancient Roman Ship

Description of Inhabitants

In his accounts, Caesar describes the population along the southern coast of Britannia to be densely populated by Belgic immigrants, who had crossed the channel from Gaul to plunder and eventually settle. There were thatch-roof, roundhouses everywhere that were similar to those in Gaul. Flocks of sheep and herds of cattle were plentiful. The inhabitants of Cantium (modern-day Kent), an entirely maritime district, were far more advanced than the inland tribes consisting of the original pastoral inhabitants who had their own traditions.

Replica of Celtic Village with Roundhouses

In common, all Britons dyed their body with woad that yielded a bluish pigment and in battle increased the wildness of their look. The men’s hair was extremely long and with the exception of the head and upper lip, the entire body was shaved.

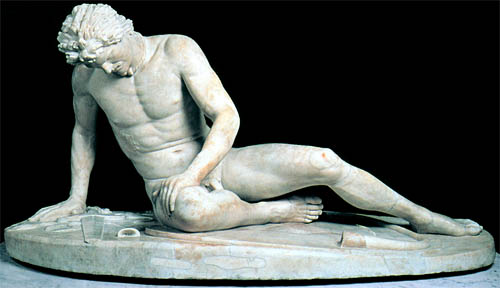

Statue of Dying Celtic Warrior

Second Landing

On 6 July 54BC, at sunset, Caesar embarked from Portis Itius (modern-day Wissant France) to Britannia with a fleet of 800 ships that transported five legions (30,000 soldiers) and 2,000 cavalrymen. The tide turned the next morning, taking the ships with it. As a consequence, the soldiers had to row the ungainly vessels without stopping to reach the Kent coast by mid-day. Unlike the first expedition, there were no signs of the enemy to oppose the landing. Caesar learned later the tribal forces had been dismayed to see the vast flotilla in the English Channel and thus decided to seek a stronger position inland to fight.

Without any opposition, Caesar’s ships anchored and a site was chosen for camp.

Shingle Beach Near Deal UK where Julius Caesar Possibly Landed

Initial Conflict

A little after midnight, Caesar marched his legions twelve miles inland to the River Stour near Canterbury. The Britons fell back to a formidable position in the woods which Caesar described as being fortified by immense natural and artificial strength. The hill-fort was strongly guarded by felled trees that were packed together. Possibly this site was initially built for tribal wars. The Roman soldiers locked their shields above their heads to form a testudo (tortoise) to protect themselves from missiles while they hacked their way into the fortress and drove the British forces into the woods. Further pursuit was forbidden by Caesar as the countryside was unfamiliar and he needed sufficient time to entrench his camp.

Celtic Shield Retrieved from Thames River

Storm’s Wrath

The following morning, the Roman pursuit of the British fugitives began in earnest. Again Caesar underestimated the powerful forces of the English Channel. A terrible storm along the coast tore the ships from their moorings and drove them ashore. When Caesar received the bad news about the shipwrecks, he abandoned his speedy advance which would have desolated the Britons and returned his army to repair the damages to his vessels.

Frieze of Ancient Warship

(To be continued)

References:

Julius Caesar, translated by F. P. Long, 2005. The Conquest of Gaul; United States: Barnes & Noble, Inc.

Graham Webster, The Roman Invasion of Britain; Reprinted 1999 by Routledge, New York.

Joseph Campbell, The Hero with a Thousand Faces; 3rd Edition Reprinted by New World Library, Novato, CA.

© Copyright May 20, 2013, by Linnea Tanner. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Rita Roberts

Posted at 01:35h, 22 MayFantastic piece of history. Thank you for refreshing my memory.

Linnea Tanner

Posted at 08:22h, 22 MayThank you, Rita, for leaving a comment. It has also been a refresher for me as I’m re-publishing these older posts. Hope you are staying well and safe.

Luciana

Posted at 21:23h, 13 JuneCaesar was clever to have his ship builders reconstruct the warships after his first failed attempt invading Britain. Always enjoy your historical posts, Linnea 🙂

Linnea Tanner

Posted at 10:39h, 14 JuneThank you, Luciana, for leaving a comment. I agree that Julius Caesar was clever to rebuilt his worships. Ironically, the storms and tides turned against him on his second excursion. I look forward to reading your third book in the Servant of the Gods Series. Have a lovely weekend! Take care, Linnea