28 Apr Julius Caesar’s Invasion of Britannia (Part 1)

Celtic Tradition of Raven:

I have fled in the shape of a raven of prophetic speech (Taliesin). The raven offers initiation—the destruction of one thing to give birth to another. For deeper understanding, the heroine must journey through darkness to emerge into the morning’s new light.

INTRODUCTION

This is a reblog of a post that was published on March 28, 2013, by Linnea Tanner on this website. The historical fantasy series, Curse of Clansmen and Kings, is envisioned to be five-book saga spanning from 24 to 40 AD in Britannia (England), Gaul (modern-day France), and Rome prior to the invasion of Claudius in 43 AD. Though Julius Caesar’s invasion of Britannia occurred eighty years earlier in 55 and 54 BC, there is archaeological evidence that his invasion was not a momentary diversion from his conquest of Gaul. Instead, it was his effort to establish the dynasties of the most powerful tribes of southeast Britain who would swear their loyalty to Rome.

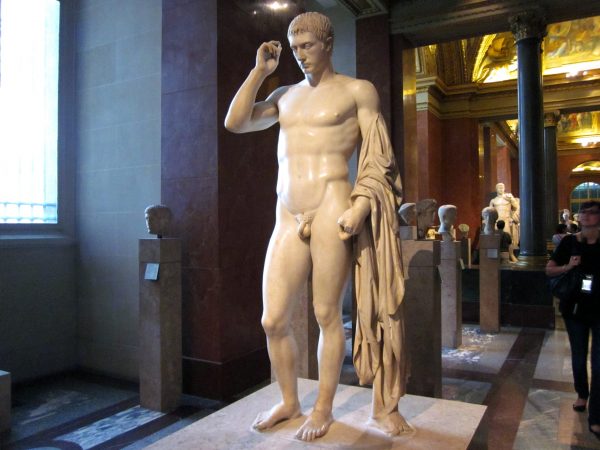

Statue Julius Caesar Displayed at Louvre Museum

The next series of posts will summarize historical and archaeological evidence of possible events that led to the Roman invasion of Britain in 43 AD. The military expedition of Julius Caesar into Britannia, occurring eighty years earlier, sets the backdrop for Rome’s foreign relationships with the Celtic rulers in Britannia. The political unrest of tribal rulers competing for Rome’s favor sets the stage for the Curse of Clansmen and Kings series. The series follows the epic odyssey of Catrin — destined to become a warrior queen of her Cantiaci kingdom — and her Roman lover, the great-grandson of Marc Antony (Marcus Antonius).

Caesar’s Invasion of Britannia

Planning

In 55 AD, Caesar decided to invade Britannia because powerful chieftains had secretly aided the Gauls in their war against Rome. Most of Caesar’s limited information about Britannia was derived from traders. Thus, he wanted to learn more about the island’s size, the harbors suitable for landing larger vessels, and the names of tribal leaders and their military state and organization. He dispatched Commius, King of the Atrebates tribe from Gaul, to impress upon the British leaders that they needed to cooperate with the Romans. A formidable general, Caesar threatened to visit them in person to assure their alliance.

Collapsed Wall of White Cliffs Near Dover 2012

As Caesar prepared his fleet to invade Britannia from a port near modern-day Boulogne France, traders informed British chieftains of his planned military expedition. Some Celtic tribes from southeast Britannia (modern-day Kent) sent envoys promising to hand over hostages to Caesar and to acknowledge Rome’s suzerainty over them. In essence, the Celtic leaders promised Caesar that Rome could control their foreign relations as a vassal state in exchange for allowing them authority over their internal affairs. Encouraged by the willingness of the Celtic rulers to negotiate, Caesar allowed the British envoys to return home.

Frieze of Roman Warship

Roman Landing

In late summer at midnight, Caesar disembarked eighty ships that were sufficient to transport two legions (about 10,000 soldiers). He left instructions for eighteen ships to transport the cavalry further north on the coastline. When his warships first reached the Britannia shores early the next morning, the whole line of hills (Dover Cliffs) was crowned with armed warriors. There was little space between the sea and rising white cliffs from which the Celtic spearmen could easily hurl their weapons down. As landing was impossible, Caesar directed his fleet to sail seven miles north to an open, flat expanse of shingled beach. The Celtic horsemen followed Caesar’s ships on the hilltops as they sailed up the coastline.

Replica of Ancient Roman Ship

Battle with Celtic Horsemen

Further north, Caesar’s forces found getting ashore to be a difficult feat. Roman soldiers were forced to jump overboard without knowing the depth of the bottom. Laden with heavy equipment, Roman troops waded through the channel’s shallow waters to get ashore. While trying to maintain their footing in the surf, the Roman infantrymen confronted Celtic horsemen that could outmaneuver them on land.

Celtic Horned Helmet Found at River Thames Date 150-50BC

At first, the Roman legionaries panicked. Then Caesar ordered the warships to hurl sling-stones, arrows, and artillery at the Celtic horsemen to drive them from their point of vantage. An eagle-bearer from the Tenth Legion emboldened his comrades by leaping into the water and shouting, “I, at any rate, shall not be found wanting in my duty to my country and general.”

Probable Site of Caesar’s First Landing Shingled Beach near Deal UK

The battle was fiercely contested. The Romans found it impossible to maintain formation, while the Celtic warriors seized every opportunity to dash in with their horses at isolated groups of soldiers struggling to get ashore. Once Caesar firmly landed the infantrymen, they charged and routed the Britons. After the Celtic army was vanquished in battle, the tribal rulers again sent envoys to Caesar and returned Commius, the King of the Atrebetas who had been originally dispatched to herald Caesar’s coming. The Celtic chieftains again promised to give Caesar hostages and to yield to his orders.

(To be continued)

References:

Julius Caesar, translated by F. P. Long, 2005. The Conquest of Gaul. United States: Barnes & Noble, Inc.

John Manley, 2002. AD 43—The Roman Invasion of Britain. Charlston, SC: Tempus Publishing Inc.

© Copyright March 28, 2013 by Linnea Tanner. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Gwen Plano

Posted at 19:01h, 28 AprilVery informative post! Thank you, Linnea.

Linnea Tanner

Posted at 09:02h, 30 AprilThank you, Gwen, for commenting on the post. Hope you have a wonderful day!

Luciana

Posted at 01:28h, 16 MayI’ve always enjoyed your historical articles, Linnea, they are informative and I always learn something new.

Linnea Tanner

Posted at 10:22h, 16 MayThank you so much for your comment, Luciana. Not only was Julius Caesar, a military commander, he also kept detailed accounts of his military expeditions. I hope you are staying safe and healthy.