31 Aug Caesar’s Invasions of Britain: Celtic Perspective

“Of the inhabitants, those of Cantium (Kent), an entirely maritime district, are far the most advanced, and the type of civilization prevalent here differs little from that of Gaul. With most of the more inland tribes, the cultivation of corn disappears and a pastoral form of life succeeds, flesh and milk forming the principal diet, and skins of animals the dress. On the other hand, the Britons all agree in dying their bodies with woad, a substance that yields a bluish pigment, and in battle greatly increases the wildness of their look. Their hair is worn extremely long, and with the exception of the head and upper lip the entire body is shaved.” (Julius Caesar’s account of Britain)

Caesar’s Invasions of Britain: Celtic Perspective

Introduction

In researching Celtic history, I ran across an interesting book entitled, “History of the Kings of Britain,” which was written in Latin by Geoffrey of Monmouth in 1136 AD. This book traces the history of Britons through a sweep of nineteen hundred years, stretching from the mythical Brutus, great-grandson of the Trojan Aeneas, to the last British King, Cadwallader. Geoffrey claims he translated his stories from “a certain very ancient book written in the British language” that was given to him by Walter the Archdeacon. Though his work has been sharply criticized for its historical inaccuracies, there are bits of truth that cannot be completely discounted.

Celtic Tribes Southeast Britain

Of particular interest is Geoffrey’s account of Caesar’s invasions of Britain and his battles with Cassivellaunus which is told from his patriotic British viewpoint. What rings true in his story is the fragility of the British rulers’ egos and their lust for power, a weakness that eventually plays into the hands of Claudius who invaded Britain in 43 AD. Previous posts that have summarized Caesar’s Invasions of Britain from his accounts are located in the archives under the categories: Julius Caesar and Roman Invasion of Britain.

Below is a summary of Geoffrey’s version. One has to wonder if there are some truths from his version that put some of Caesar’s accounts into question.

Geoffrey’s Account of Caesar’s Invasions of Britain

Julius Caesar was fascinated with Britain as he had been told the Britons were founded by Brutus, a descendant of Aeneas who fled from the ruined city of Troy to Italy. Although the Romans were descended from the same ancient Trojan stock as the Britons, Caesar underestimated the Britons, believing it would be a simple matter of forcing them to pay tribute and to swear their perpetual obedience to Rome. Thus, Caesar dispatched a message to the British King, Cassivellaunus, with the demand that he pay tribute.

After reading Caesar’s message, Cassivellaunus became indignant and sent Caesar a written message that he refused to accept his terms of slavery. He further says, “It is friendship which you should have asked of us, not slavery. For our part, we are more used to making allies than enduring the yoke of bondage…we shall fight for our liberty and for our kingdom.”

The moment Caesar read this letter he prepared his fleet to set sail to Britain.

Collapsed Wall of White Cliffs Near Dover Photographed in 2012

King Cassivellaunus—along with his brother Nennius, his nephew Androgeus (Duke of Trivovantum), and other nobles—marched down to meet Caesar after he had landed and set-up his Roman camp near the Dover Cliffs. A fierce hand-to-hand battle ensued. In single combat, Caesar cut his sword into Nennius’ shield that he could not wrench out. Nennius, taking Caesar’s sword, raged up and down the battlefield killing everyone he met. The Britons pressed forward as a united front cutting the Roman forces into pieces. That night, Caesar reformed his ranks, boarded his ships, and sailed back to Gaul in defeat. Nennius succumbed to his wounds fifteen days after the battle and died. Cassivellaunus buried him with Caesar’s sword called Yellow Death, for no man who was struck by it escaped alive.

Celtic Swords Displayed at the British Museum

Two years later, Caesar prepared to cross the sea a second time to avenge Cassivellaunus for the humiliating defeat he had suffered at his hands. As soon as the king heard of this, he garrisoned villages everywhere and planted stakes shod with iron and lead below the water-line in the bed of the River Thames, up which Caesar would have to sail to attack Trivovantum.

Replica of Celtic Village with Roundhouses

Cassivellaunus and every man of military age waited for Caesar to cruise up the Thames where his ships were ripped apart by the stakes. As a result, thousands of Romans drowned, but several survivors clambered with Caesar onto dry land. The King ordered his warriors to charge the remaining Romans. The Britons, outnumbering the Romans three to one, were victorious over their weakened enemy. Again, Caesar escaped to his remaining undamaged ships and sailed back to Gaul.

Elated from his overwhelming victory, Cassivellaunus invited all his noblemen to a glorious feast where cows, sheep, fowl, and wild beasts in the hundreds were sacrificed as offerings to the gods. At the sporting events that night, the king’s nephew was beheaded by the nephew of Duke Androgeus as a result of a dispute. Cassivellaunus demanded that the Duke present his nephew in court for sentence. Androgeus refused.

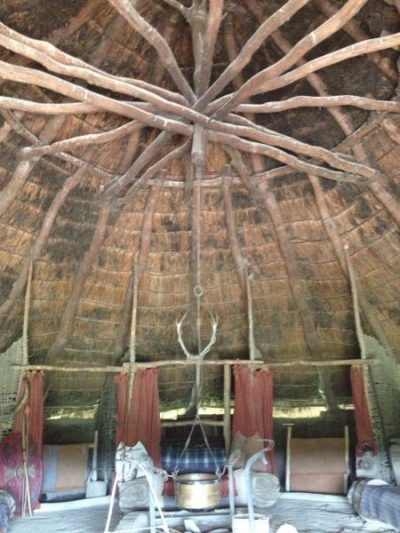

Inside of Replica of Celtic Roundhouse for Chieftain

Enraged by the Duke’s refusal, Cassivellaunus ravaged his lands. In desperation, Androgeus dispatched a message to Caesar with a plea to help him restore his position. Only after the Duke sent his son, together with thirty young nobles as hostages, did Caesar depart for Britain a third time.

Replica of Ancient Roman Ship

This time, Cassivellaunus was sacking Trinovantum when Caesar landed. Upon hearing the news of Caesar’s return, the king abandoned his siege and rushed to meet his Roman adversary. When the two sides met, they hurled deadly weapons at each other and exchanged mortal blows with their swords. In an unexpected move, Androgeus and his forces attacked the rear of the king’s battle line, forcing his warriors to give ground from the assaults on both sides.

Cassivellaunus took flight from the battlefield and retreated to a hillfort. Caesar besieged the hillfort but still couldn’t defeat the king. Even now, when driven off the battle-field, Cassivellaunus and his battered forces continued resisting a man whom the whole world could not withstand. Caesar resorted to cutting off all means for the King’s retreat to starve them.

Example of Ancient Celtic Hillfort (Maiden Castle Dorchester)

After two days without food, Cassivellaunus sent a message asking Androgeus to make peace for him with Caesar. When the envoys delivered the message to Androgeus, he said, “The leader who is as fierce as a lion in peace-time but as gentle as a lamb in time of war is not really worth much.” Nonetheless, he was moved by the king’s pleas and went to Caesar to plead mercy for Cassivellaunus. Androgeus told Caesar, “All that I promise you is this, that I would help you humble Cassivellaunus and conquer Britain. He is beaten, and, with my help, Britain is in your hands. Yet I cannot allow you to kill him while I myself remain alive.”

Celtic Carnyx Serpent War Horn

Ultimately, Caesar made peace with Cassivellaunus who, in turn, promised yearly tribute to Rome. The tale ends well as Caesar and Cassivellaunus become great friends and give each other gifts. Androgeus travels to Rome as a guest of Caesar.

Concluding Remarks

Certainly, the above tale of Caesar’s Invasions of Britain differs from the Roman General’s account, but there are some similarities. Caesar wrote that, after Cassivellaunus brought down the King of the Trinovantes, his son Mandubracius fled to Gaul. Mandubracius begged for Caesar’s help in regaining the Trinovantes kingdom. On Caesar’s second invasion of Britain in 54 BC, Cassivellaunus fiercely resisted the Romans, but he eventually surrendered after they devastated his territories and other rival kings sought peace with his enemy.

Though Caesar was proclaimed a hero by the Roman Senate for his accomplishments in Britain, it can be argued his expeditions were not successful, for he did not complete the conquest. The scenario of British rulers fleeing to Rome and asking for help to regain their sovereignty from rival rulers repeats time and time again, up to the final conquest by Emperor Claudius in 43 AD. At that time, the King of the Atrebates, Verica, asked for help from Claudius in regaining his territory from Caratacus, an anti-Roman chieftain from the Catuvellauni tribe.

Richborough Roman Fort Ruins

To be continued

The next posts will provide an overview of rival dynastic kings that came to power in Britain between the time period of Caesar’s invasion of Britain in 54 BC up to Claudius’ conquest in 43 AD.

References:

Geoffrey of Monmouth, The History of the Kings of Britain, translated with an introduction by Lewis Thorpe; Penguin Books, New York; first published 1966.

Julius Caesar, The Conquest of Gaul, translated by Rev. F. P. Long and introduction by Cheryl Walker; Barnes & Noble, Inc., New York; 2005.

©Copyright August 31, 2015, by Linnea Tanner. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Tom

Posted at 20:41h, 31 AugustJust got the post. Good Job!

Linnea Tanner

Posted at 07:11h, 03 SeptemberThanks, Tom, for letting me know. Hopefully, everything has been worked out for receiving my posts. Have a fabulous week!

Regards,

Linnea

Brenda Spangler

Posted at 07:25h, 01 SeptemberAs I read the article, thought about why the Romans would have wanted what we refer to as modern Britain, and then remembered they wanted the tin mines. Good outline. Thanks!

Linnea Tanner

Posted at 21:30h, 01 SeptemberHi Brenda,

Thank you for your feedback. It is true, as you indicated, that Wales was rich in tin and other metals which the Romans wanted. There were a couple of times that Emperor Augustus thought about conquering Britain but he had his hands full with resistance from Germanic tribes. Roman treaties with some of the powerful British rulers also dissuaded invasion until anti-Roman factions came into play around 40 AD.

Again, I appreciate your feedback. Have a great day!

Best wishes,

Linnea

Aquileana

Posted at 02:57h, 03 SeptemberExcellent post… It was very interesting to learn about the Celtic perspective with regard to Caesar’s invasion as retold by Geoffrey of Monmouth in his “History of the Kings of Britain”… The concluding remarks offer a good summary…. Very eloquent and intriguing… I am looking forward to the next installment, dear Linnea…

Thanks so much for sharing! Best wishes. Aquileana 😉

Linnea Tanner

Posted at 07:10h, 03 SeptemberThank you again, Aquileana, for your feedback and gracious support. I’m glad you enjoyed it! I appreciate your continuing support and sharing your love of mythology. Have a fabulous week!

Regards,

Linnea

Aquileana

Posted at 02:58h, 03 SeptemberExcellent post… It was very interesting to learn about the Celtic perspective with regard to Caesar’s invasion as retold by Geoffrey of Monmouth in his “History of the Kings of Britain”… The concluding remarks offer a good summary…. Very eloquent and intriguing… I am looking forward to the next installment, dear Linnea.

Thanks so much for sharing! Best wishes. Aquileana 😉

Linnea Tanner

Posted at 07:09h, 03 SeptemberThanks, Aquileana, for your feedback and gracious support. I’m glad you enjoyed it. Have a fabulous week!

Regards,

Linnea

Luciana

Posted at 06:40h, 09 SeptemberHi Linnea,

A great post and interesting to read a different perspective as opposed to the Roman viewpoint on how battles were won. Caesar was, as you know, renown for exaggerating and promoting his successes. I’ve read his version on the invasion of Gaul, fascinating and he certainly knew how to spin his achievements. ;D

I look forward to the next part in the series.

Cheers

Luciana

Linnea Tanner

Posted at 01:49h, 10 SeptemberHi Luciana,

Thank you for your comments, particularly you comments that Caesar’s accounts were highly exaggerated about his success. Ancient historical accounts always need to be read with caution as there may be political reasons for the way it is presented. Although the tales by Geoffrey of Monmouth is also questionable on its accuracy, there is probably some truth that Caesar had more effective opposition from the Britons than he admitted in his accounts. The Celtic point of view was certainly a more enjoyable read.

I always appreciate your comments and sharing our love of mythology.

Cheers,

Linnea

Cathleen Townsend

Posted at 00:37h, 27 SeptemberAn excellent article–both informative and interesting. Thanks for sharing. 🙂

I’d only read historical accounts of this from the Roman POV before.

Linnea Tanner

Posted at 06:59h, 28 SeptemberThanks, Kathleen, for your feedback. It is always interesting to get the perspective of the other side in an historical account. I am glad you enjoyed the articles.

Best wishes,

Linnea

Tim Vicary

Posted at 20:11h, 20 OctoberBeautifully told and presented. A pleasure to read.

Linnea Tanner

Posted at 04:08h, 21 OctoberHi Tim,

I appreciate your positive comment. It is interesting to view this from a Celtic perspective.

Best wishes,

Linnea