25 Feb Golden Age of Celts: Status Built by Battle or Feast

The whole race [Celts] is made for war. High-spirited and quick to battle.

— Strabo, Greek Historian

GOLDEN AGE OF CELTS

Status-Building in Battle

During the Golden Age of the Celts (Le Tène Period), cattle thievery, slave raiding, and vendettas between clans and tribes formed the basis of low-intensity warfare that permeated the Celtic society. Such conflicts were a starting point for a young warrior to demonstrate his bravery and skills at weapon-handling. In a society that took personal courage for granted, something more was required to establish a reputation.

One way was to serve as a mercenary in many of the various armies during the classical period. Renowned Celtic mercenaries served Hannibal during his invasion of Italy in the Second Punic War. The Celtic invasion helped establish Rome’s image of Celts as fierce warriors. They also fought in Greek armies and successor kingdoms following the break-up of Alexander’s empire in Egypt.

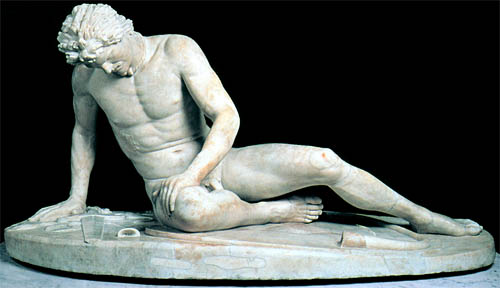

Statue of Dying Celtic Warrior

A distinct group of Celtic mercenaries called the Gaesatae joined the Cisalpine Gauls in the battle of Telemon against the Romans. These mercenaries were outside the normal social structure of the clan and tribes. The Celtic word geissi—bonds, taboos, or sacred rule of conduct—suggests these warriors had a strong spiritual aspect to their life, which will be further examined in later posts. It was the custom of Gaesatae to fight naked in battle as a ritual act.

Location of Battle of Telemon

Clearly, many Celts looked for fame and future in the lucrative Mediterranean world with the hope of returning home with their reputations established. Mercenary service also removed young warriors from the tribe when their drive to achieve high status was at their most intense. Control of imported goods, especially gold coins and Italian wine, also guaranteed a large fortune.

Potlach

Previous posts highlighted that trade with the Mediterranean had a significant impact on Celtic society. Nobles rewarded warriors and other clients with foreign luxuries, the value of which was measured by the influence it could command by giving it away. This method of redistributing prestigious items to increase status is called potlatch.

The 1st Century BC Greek historian, Poseidonius, writes that Lovernius, a Celtic noble who attempted to win popular support by driving his chariot across his territory and distributing gold and silver to those who followed him. Moreover, a noble set-up separate enclosures one and one-half miles on each side. He filled vats with expensive liquor and prepared food for all who wished to feast—an important social gathering that was not unlike today’s celebrations. The feasts were usually wild and drunken, but strict ritual rules were obeyed.

Celtic Roundhouse for Assembly

Wild Celtic Feasts

Strict ceremonial rules were observed for seating participants according to rank and prowess. Poseidonius describes the arrangement as follows:

“…they sit in a circle with the most influential man in the center, whether he is the greatest in warlike skill, was the nobility of family or wealth. Beside him sat the host, and on either side of them were others in order of distinction. Their shield bearers stood behind them while the spearmen were seated on the opposite end. All feasted in common with their lords.”

Central Hearth in Celtic Roundhouse

Also in attendance were bards who sang praises of their patrons’ lineage, bravery, and wealth. Their songs could praise and satirize their patron, thus encouraging nobles and warriors to be even more generous during the feast. Strangers could also share the meal before they were asked their name and business.

Celtic Swords Displayed at British Museum

Everyone had a piece of meat according to their status. Traditionally, the greatest warrior had the choicest cut, consisting of the thigh. When the hindquarters were served, another warrior could claim it and fight in single combat to the death against the champion to elevate his status. Others sought to reinforce their status through mock battle engagement that might escalate into more serious violence, possibly death. Poseidonius writes:

“The Celts engage in single combat at dinner. Assembling in arms, they engage in mock battle drills and mutual thrust and parry. Sometimes wounds were inflicted, and the irritation caused by this may even lead to the killing of the opponent unless they were held back by their friends.”

Conclusions

According to Caesar, the bravery of the Celts sprang from their lack of fear of death. This was because Celtic believed the soul does not die. The classical authors, Caesar, Lucan, and Diodorus Siculus, in particular, emphasized the Celtic belief in metempsychosis. At death, the soul passes from one body to another in reincarnation. This belief may, in part, explains why Celts felt it was important to establish their status in preparation for the journey to the Otherworld.

Not only did Celtic men fight bravely in battle, but historical accounts and mythology provide evidence that women held equal standing to men and often fought in battles and served as military and spiritual leaders. This will be discussed in the next post.

References:

John Davies, The Celts: Prehistory to Present Day; 2005. United States: Sterling Publishing Co., New York.

Stephen Allen, Celtic Warrior: 300 BC-AD 100; 2001. Osprey Publishing LTD., Westminster, MD, USA.

Julius Caesar, translated by F. P. Long, 2005. The Conquest of Gaul; United States: Barnes & Noble, Inc.

©Copyright February 25, 2014, by Linnea Tanner. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Tom

Posted at 15:05h, 25 February“Optimist: day-dreamer more elegantly spelled.” Mark Twain

I enjoy all the Wisdom I get from reading your work. Thanks,

Linnea Tanner

Posted at 16:30h, 25 FebruaryThanks, Tom, for your comment. Interesting comment from Mark Twain.

Luciana

Posted at 06:35h, 20 MarchMercenaries were always in it for the money and had a reputation for betraying their homeland especially if they fought against their own people. It is interesting to read the Celts did it for prestige and gaining wealth. I wonder how many returned home successfully?

A great post Linnea 😀

Linnea Tanner

Posted at 15:00h, 20 MarchThanks, Luciana for your comment. One aspect that did lead to the downfall of the Celts was their inability to unify tribal kingdoms to defeat a common enemy such as the Romans. Some of this could be attributed to their culture where warriors and chieftains were in constant competition with each other. There were a few leaders, including the British warrior queen Boudicca, who did manage to unify different tribes to confront the Romans, but they were ultimately defeated.

Peggy Knox

Posted at 04:06h, 31 JulyNice post. I learn something totally new and challenging on sites I stumbleupon everyday. It’s always interesting to read through articles from other authors and use a little something from their websites.

Linnea Tanner

Posted at 20:39h, 31 JulyHi Peggy,

Thank you for visiting APOLLO’S RAVEN and your gracious comment. I always appreciate any of your thoughts and feedback to the articles.

Best wishes,

Linnea