26 Apr Caesar’s Invasion Celtic Britain 1st Expedition (Part 2)

The Call to Adventure: The first stage of the mythological journey—designated as the ‘call to adventure’—signifies destiny has summoned the hero and transferred his spiritual center of gravity from within the pale of his society to a zone unknown—Joseph Campbell

INTRODUCTION

Based on historical and archaeological evidence, there is evidence that Julius Caesar’s invasion in 55-54 BC helped to establish dynasties in the two most powerful tribes of southeast Britain who pledged their loyalty to Rome. Below is a continuation of Caesar’s first expedition to Celtic Britain in 55 BC (Part 2).

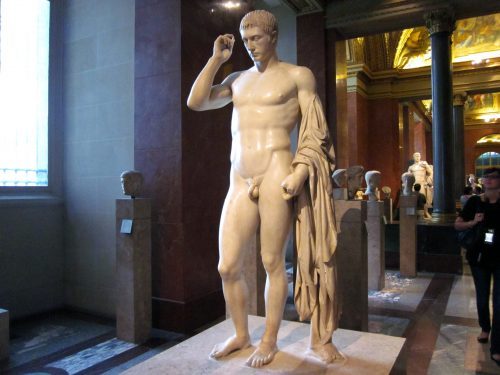

Statue of Julius Caesar

Caesar’s Invasion Celtic Britain: First Expedition

Tidal Phenomena

After Caesar defeated the Britons near the Kent coastline, the tribal leaders surrendered, promising to serve his every need and to let him use the natives at his disposal. On the fourth day of the Roman expedition, eighteen ships carrying the cavalry were driven back by a sudden storm. On the same night, the full moon brought a tidal phenomenon that Caesar was not prepared to face. Waves surged up the beach and destroyed or damaged most of his ships. Caesar ordered some of his soldiers to repair the damaged ships using the timber and copper from the worst wrecks while he directed others to forage for corn in the surrounding fields.

Replica of Ancient Roman Ship

There was a marked change in the attitude of the Celtic chieftains who secretly met and pledged to take up arms again and starve out their invaders. They covertly called upon their followers to fight. Caesar was unaware of their treachery as there had not been any suspicious hostile movements by local inhabitants who continued to farm and to visit the Roman encampment. That all changed when outposts outside the main camp reported to Caesar that there was a cloud of dust in an area that had been taken by the Romans. Now suspecting a new plot had broken among the natives, Caesar ordered a battalion to march a considerable distance to where Celtic warriors in chariots had ambushed some of his soldiers foraging for food.

Pathway Along Dover Cliffs

Chariot Fighting

Caesar had not previously encountered chariot fighting which threw his infantrymen into dire confusion. The Celtic charioteers, galloping wildly down the whole field of battle, terrified the Roman soldiers by charging their horses into the melee of fighting. A Celtic warrior would leap out of the chariot and fight on foot. Meanwhile, the driver positioned a short distance from battle to retreat whenever they became overpowered. Thus, the Celts combined the skill of an infantryman with the mobility of the cavalry. Even on the most treacherous terrain, the charioteers had perfect control over their horses.

Replica of Celtic Chariot at Colchester Castle

Final Roman Victory

Though these chariot-fighting tactics challenged the military discipline of the Romans, Caesar returned back to camp with his remaining troops. In the meantime, news of Rome’s weakness and an appeal to expel the invaders from their entrenchments spread throughout the countryside. Caesar resolved to crush the advancing enemy forces on foot and horse by charging them with two legions. The Celtic warriors could not withstand the Roman attack and many of them were killed. Several of the villages and farms were burned to ashes.

Celtic Village with Round Houses

Tribal leaders agreed to surrender under the terms that the number of hostages previously imposed would double. With the equinox close on hand, Caesar feared his repaired ships might not withstand the ocean’s storms and thus he sailed back to the Continent with a few of the hostages. When he ordered the remaining hostages from Britain, most of the tribes refused to send them.

During the following winter months, Caesar ordered his generals to build a fleet of newly designed ships that could better handle the seas in the British Channel for his next invasion.

Frieze of Roman Warship

(To be continued)

References:

Julius Caesar, translated by F. P. Long, 2005. The Conquest of Gaul; United States: Barnes & Noble, Inc.

John Manley, 2002. AD 43—The Roman Invasion of Britain. Charlston, SC: Tempus Publishing Inc.

Graham Webster, The Roman Invasion of Britain; Reprinted 1999 by Routledge, New York.

Joseph Campbell, The Hero with a Thousand Faces; 3rd Edition Reprinted by New World Library, Novato, CA.

© Copyright April 26, 2013, by Linnea Tanner. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Jim Hatcher

Posted at 04:34h, 27 AprilI would have never guessed that the Celt introduced the Romans to chariot warfare. Interesting stuff.

Rita Roberts

Posted at 11:15h, 18 MayLove Roman history . This is where I gained my first A level Thanks for this post Linnea. really enjoyed it.

Linnea Tanner

Posted at 12:28h, 19 MayThank you for commenting, Rita. I’m also fascinated with Roman history as some of their issues then are true today. I’m always fascinated with ancient archaeology on your blog. Take care and keep safe.