20 Mar British Kings Atrebates

Cities and Thrones and Powers

Stand in Time’s eye,

Almost as long as flowers,

Which daily die,

But, as new buds put forth

To glad new men,

Out of the spent and unconsidered Earth,

The Cities rise again

—Rudyard Kipling

Introduction

Julius Caesar described some of the tribal kingdoms in southeast Britannia (Britain) as identical to those in Gaul (modern-day France), but he does not specify which ones. Much of the population was divided into named units in the order of tens of thousands of people which were called civitates, usually translated as ‘tribes’ or ‘states’.

Celtic Gold Torc

It is striking that most of the tribes that Caesar mentioned in his accounts vanished by the time of Claudius’ invasion in 43 AD. Archaeological finds, particularly coins minted by the British kings, suggest great instability and volatility in the ever-expanding dynastic states. Coin evidence is no substitute for detailed political accounts. Nevertheless, it provides us with the earliest names of the players in the political struggles. Coins also provide a crude indicator of tribal territories, alliances, and the political geography of southern Britannia. The power struggles between pro- and anti-Roman factions play a crucial role in triggering the Roman invasion in 43 AD.

Celtic Tribes in Southeast Britannia

One of the most powerful British tribal kingdoms was the Atrebates that was also a tribe in Gaul. King Commius fled to Britannia after Caesar’s conquest in Gaul to establish this powerful dynasty. Below is a tabular summary of British kings who minted coins in the southern and northern dynasties.

British Kings in Southeast Britannia

| Date | Rome | Southern Dynasty | Northern Dynasty |

| 50 BC | Civil War, Murder of Caesar; | ||

| 40 BC | Commius | ||

| 30 BC | Octavian and Mark Antony Civil War | Addedomaros | |

| 20 BC | Augustus | Tasciovanus | |

| 10 BC | Tincomarus | Dubnovellaunos | |

| 1 AD | |||

| AD 10 | Epatticus | Cunobelin Vodenos |

|

| AD 20 | Tiberius | Eppillus | |

| AD 30 | Verica | Adminius | |

| AD40 | Caligula | Caratacus | |

| AD50 | Claudius |

Commius of the Atrebates

Alliance with Caesar

Julius Caesar considered Commius one of his strongest Celtic allies in Gaul where he made him King of the Atrebates. In 55 AD, Caesar sent Commius as a diplomatic emissary to Britannia to win their loyalty to Rome. The tribal leaders who Caesar had in mind were those that had fled from Gaul during his military campaign. The moment Commius disembarked on the shores of Kent and announced his mission, he was taken as a prisoner. Later that summer, he was handed back to Caesar in his first expedition to Britannia. Commius then went with Caesar on his second expedition to Britannia where he helped with the peace negotiations.

Replica of Celtic War Chariot

Resistance with Vercingetorix

In spite of winning Caesar’s favor, Commius allied with Vercingetorix and was appointed as one of his chief officers in a united Gallic resistance against Caesar in 52 BC. After Caesar’s great victory over Vercingetorix at Alesia, Commius escaped the battle with the aid of the Germans.

Statue ofVercingetorix

Caesar sent a special team to execute Commius, but he managed to escape with a severe head wound. He avoided yet another encounter with Roman executioners at a party. After that, he sailed to southeast Britannia with a band of his followers. Again, he eluded the Roman ship that was pursuing him.

Frieze of Roman Warship

Atrebates Southern Dynasty

Commius landed on the British Sussex coast and established himself as King of the Atrebates. He established his capital at Calleva (Silchester). There may have already been an Atrebates tribe in Britannia that accepted Commius as their king. Commius coinage was widespread, suggesting his authority spread over a large area north of the Thames, Hampshire, and Sussex.

Abrebates British Slater

Tincomarus

Tincomarus, son and heir of Commius, ascended to power around 20 BC. Roman Emperor Augustus scored a great diplomatic triumph winning over the son of the man who hated the Romans. Tincomarus issued coins that more closely resembled the Roman types.

Based on the imagery used on his coins, Tincomarus may have been brought up as an obses (diplomatic hostage) in Rome during the early years of Augustus’ reign. It is conceivable that he gained experience in the Roman army before his return to Britain in 20 BC. He most likely established trading and diplomatic links with Augustus as evidenced by Roman pottery and other imports that have been dug up at Calleva.

Celtic child in Ara Pacis Augustae (Altar of Augustan Peace)

Augustus maintained diplomatic links in Britannia to ensure the southeast region stayed in the hands of friendly tribes. To the north was the ambitious and aggressive Catuvellauni tribe (their name means ‘Men Good in Battle’). To keep them in their place, Rome cultivated their southern rivals, the Atrebates. As far as the Romans were concerned, the rest of Britannia and Ireland beyond the trading gateway were remote and thus irrelevant.

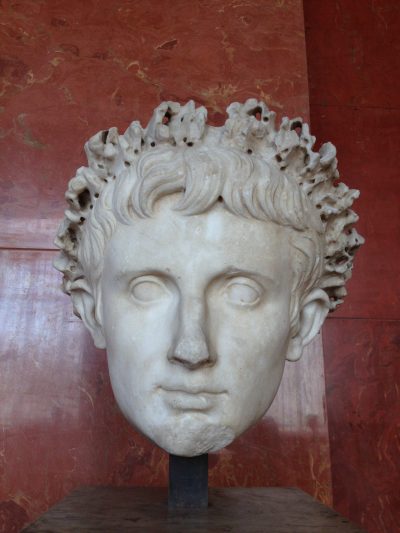

Bust of Augustus Caesar

Sometime before 7 AD, Tincomarus was driven out of his kingdom for unknown reasons and fled to Rome as a refugee. His expulsion may have resulted from a family dispute with his brother, Eppillus. Tincomarus appeared before Augustus as a suppliant king. Augustus recognized Eppillus as REX (king) rather than depose and reinstate Tincomarus. Augustus may have planned to use his ally’s ejection as an excuse to invade Britannia but other more pressing foreign policy matters took precedence.

Celtic Shield Retrieved from Thames River

Epillus and Eppaticus

Epillus’s rein over the Atrebates was short-lived. Eppaticus, the brother of Cunobelin (Catuvellauni tribe) most likely expelled Eppillus with the support of the anti-Roman Druids. Eppaticus managed to establish himself over the Atrebates at the time Rome was preoccupied with its own troubles about 10 AD.

Verica, the grandson of Commius, regained the throne from Eppaticus who he subsequently killed.

Post-Augustus Policies and Trade

Upon his death in 14 AD, Augustus instructed his successor, Tiberius, not to expand the Empire. Tiberius accepted this policy since he was weary of many years of warfare and maintaining order over conquered regions.

By then, Cunobelin most likely signed a formal treaty with Rome. This is implied by the Greek historian Strabo who states in 14 AD, “With important export duties, Rome receives greater profit than any army could produce.” Strabo listed British exports as grain, cattle, gold, silver, iron, hides, slaves, and hunting dogs. The general philosophy was that treaties with client kings made Rome’s position in Britannia so secure that there was no longer any need for Rome to invade.

During the campaigns on the Rhine under Germanicus in AD 16, some warships were blown across the North Sea and wrecked on the British coast. These were returned, clearly indicating a friendly gesture from one of the tribes, perhaps under a treaty obligation.

Bust of Roman Emperor Tiberius

To be Continued

Upcoming posts will provide an overview of the final political upheavals after 25 AD that triggered Rome’s Invasion of Britannia.

References

- John Peddie, Conquest: The Roman Invasion of Britain; St. Martin’s Press, New York, 1997.

- John Manley, AD43 The Roman Invasion of Britain; A Reassessment; Tempus Publishing, Inc., Charleston, SC, 2002.

- David Miles, The Tribes of Britain; Phoenix, an imprint of Orion Books, LTD, London, 2006

- Graham Webster, Boudica: The British Revolt Against Rome AD 60; Routledge, London, 2004

- Graham Webster, Rome Against Caratacus; The Roman Campaigns in Britain AD 48-58; Routledge, London, 2003

- Graham Webster, The Roman Invasion of Britain; Routledge, New York, 1999.

©Copyright March 20, 2016 by Linnea Tanner. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Aquileana

Posted at 10:26h, 22 MarchExcellent post, dear Linnea…

Who would have thought that coins might provide such an accurate historical perspective concerning the facts that were happening by then?… (not me!)

I much enjoyed the account and was particularly interested to learn about Commius and his heir Tincomarus.

Most times, History teaches us that sons and relatives must carry the burden coming from defeats and mistakes of their predecessors… And it seems the case you brought to the table is not an exception…

Thanks for the great reading…

All my best wishes. Aquileana ?

Linnea Tanner

Posted at 19:00h, 22 MarchHi Aquileana,

Thank you for your comments. It is interesting that coins minted by British kings had to fill in most of the gaps as to who ruled between Caesar and Claudius. Archaeologists are able to determine quite a bit based on design and where the coins were minted. Commius was a fascinating character as he played both sides of the fences with Caesar, but then his son had close alliance with Rome.

Again, I appreciate your support and sharing our love of mythology.

Regards,

Linnea

Annis Pratt

Posted at 14:05h, 29 MarchDear Linnea,

This is great scholarship, not so often encountered these days. I am trying to figure out whether these Gallic tribes were Celts – they were, were they not? That expands my view of Celtic political territory quite considerably.

Annis

Linnea Tanner

Posted at 16:13h, 29 MarchHi Annis,

Thank you for your lovely comment. In answer to your question, the southeastern tribes of Britain were considered Celtic. At their height in approximately 300 BC, the Celts ranged from Ireland across northern Europe to Turkey. They had a common language and art form, but certainly there were regional differences. It seems the southeastern tribes of Britain evolved differently from Ireland, Wales, and Scotland. Even before the Roman invasion of Britain in 43 AD, the Empire had a strong influence over the politics and culture of the southeastern tribes. The Romans had a much tougher time subjugating Wales and northern England and finally gave up trying to subdue Scotland and never invaded Ireland.

Again, thank you for your comments. I’m always interested in learning more about your research.

Best regards,

Linnea

Christy Birmingham

Posted at 18:30h, 16 AprilI do admire the thorough way you explain historical events and leave us wanting more at the end of the post, Linnea! Thank you for your attention to detail and explaining about the coins – I am learning so much from the reads here! Wishing you a beautiful weekend, my friend.

Linnea Tanner

Posted at 19:19h, 16 AprilThanks, Christy, for your lovely comments. I’m glad to you enjoyed this. Have a great weekend my friend,

Regards,

Linnea

Luciana

Posted at 08:48h, 11 JuneHi Linnea,

It’s been a while since I’ve visited your blog and never fail to enjoy reading your informative posts. The Celts have long been a fascination for me and am learning a great deal from your articles.

Have a great weekend, my friend.

Regards,

Luciana

Linnea Tanner

Posted at 12:46h, 11 JuneHi Luciana,

Welcome back to my site and for reblogging this article. It has always been a pleasure to share our love of ancient history and mythology. You have been an inspiration to me as an author and source of knowledge of ancient civilization.

Thanks you again, my friend, for your support.

Regards,

Linnea

Pingback:British Kings Atrebates

Posted at 18:03h, 03 February[…] Below is a reblog of an article entitled, “Atrebates British Kings” that was originally posted on my previous website on March 20, 2016. The article is an overview of some of my research in preparation for writing the historical fantasy series, Curse of Clansmen and Kings. The books in this series are set in the historical backdrop of 1st Century southeast Britannia (modern-day England). Below is an overview of competing kings in the Atrebates tribal kingdom after Julius Caesar’s invasions in 54-55 BC up to 25 AD (twenty years prior to Claudius’ conquest in 43 AD). The article is provided below in its entirety. For the original post, click British Kings Atrebates. […]